Members of the Angulo Ramirez family pose for a family portrait in the deserted building in which they take refuge. The family of 9 was displaced 3 years ago and has lived since above the market of Condoto not being able to have a house to stay in.

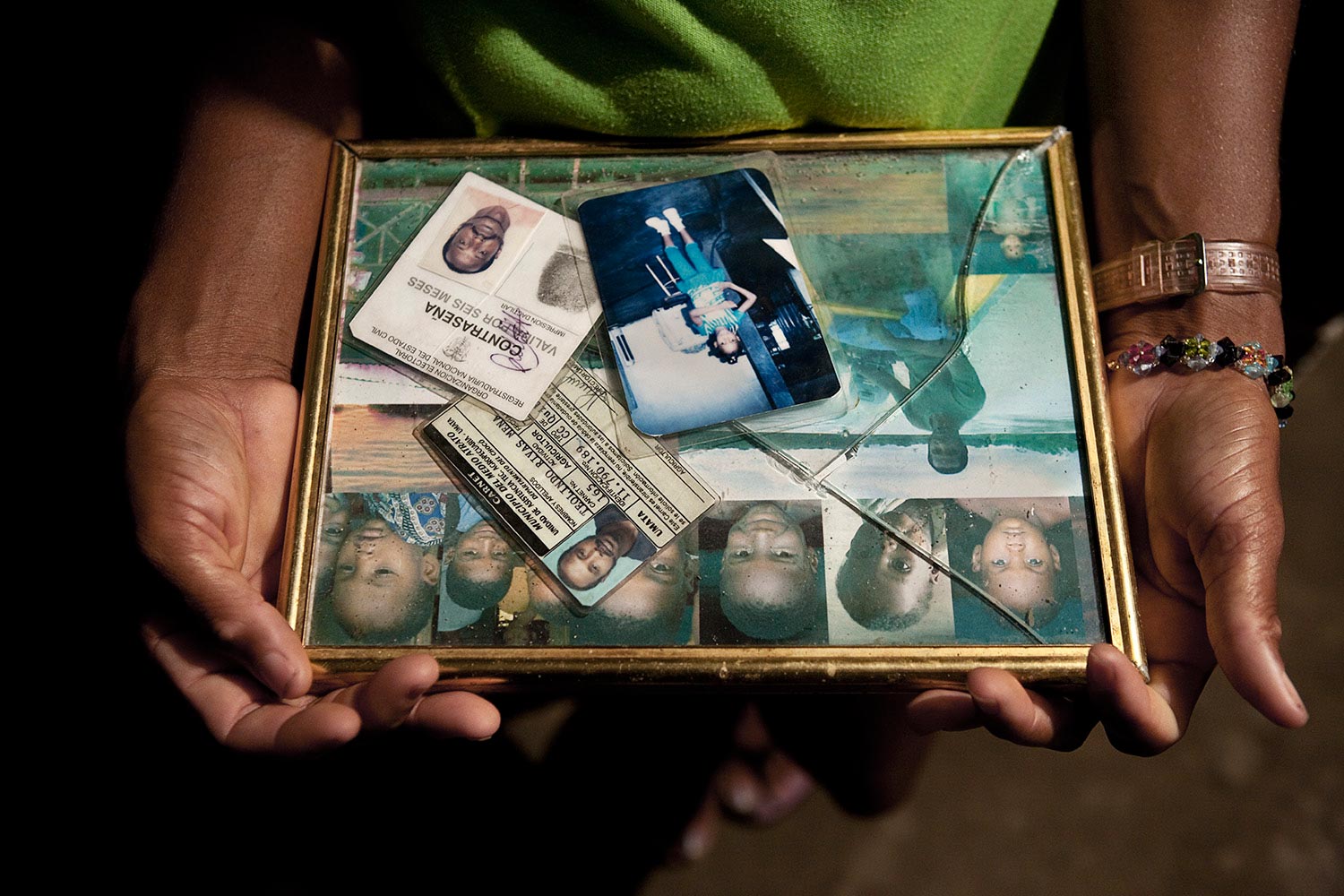

Suninda Parilla Chavera (32) holding a framed collage of pictures of her six children and murdered husband in her home in Quibdo. Suninda's husband, Teolindo Rivas Mosquera, was the leader of the community of Tangi on the Rio Atrato. Teolindo was executed by the guerilla in front of his family, which was displaced to the city of Quibdo. Suninda currently lives with two of her sons and supports the others, which live with relatives in Venezuela.

A man and a girl in the village of Bebedo along the river near Istmina in Choco. Bebedo's inhabitants live under constant threat of being displaced either due to violence from the FARC or the river flooding the village.

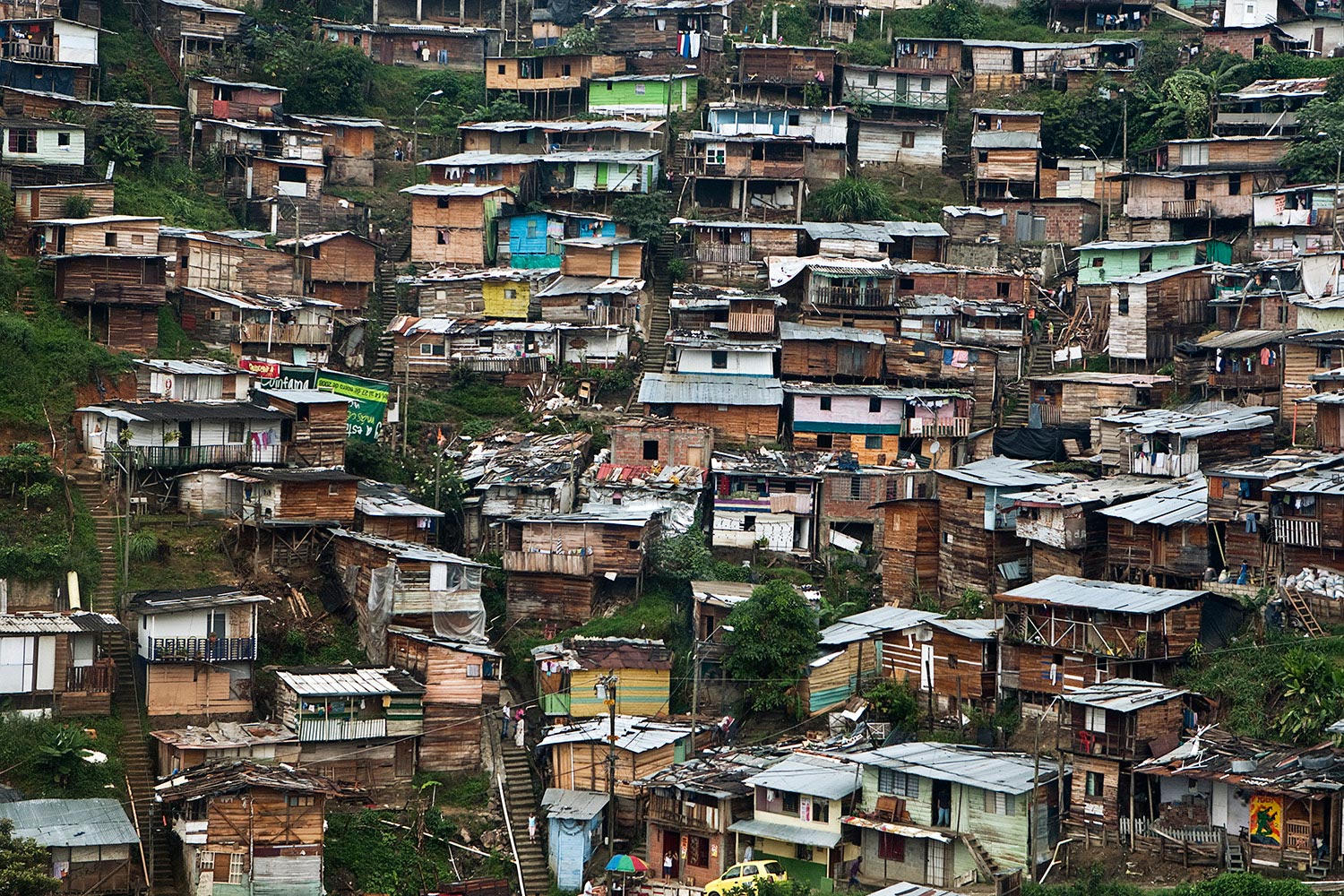

A view of 'Altos de la Virgen' (heights of the virgin) neighborhood in Medellin. The larger portion of the displaced people flee to the main cities and inhabits condensed illegal or cheep lands, building basic huts of any possible material.

Wet laundry on the roof of a house in 'Esfuerzos De Paz #1' neighborhood in Medellin. According to a 2008 report, the displacement situation has been most critical in the region of Antioquia where there was a 105% increase of displaced people during 6 months, most of which have fled to Medellin.

Emiro Moreno Romero (17) looks for scrap washed by the river next to Moravia neighborhood in Medellin. Some of the displaced population works next to the river in recycling, making little money in order to survive. Finding work is extremely difficult, and people often have to deal with exploitation and corruption.

The deserted house of the family of Teolindo Rivas Mosquera who was executed by the guerilla. Teolindo,the leader of the community in Tangui, was murdered in front of his family which was forces to leave the area. Many families are forces on a regular basis to leave their houses in fear of the guerrilla or paramilitary groups especially after key figures are murdered to establish the armed groups domination over a territory.

Yarenci Palaso Palacios (12, R) and her sister Sirley (14, L) wash the laundry in the back of their home in Quibdo. Yarenci and Sirley's family members are among the survivors of the massacre in Bojaya in 2002 and have lived in Quibdo since.

Ana Lucia Palacios Mertinez (52) in the hammock with two of her grandsons Edwin David (3) and Jesus David (1) in their hut in Quibdo. Ana's family was displaced in 2002 from Mongito by the guerrilla forces and she has lived in Quibdo since.

Juan Alberto Juarez (52) holding a few rusty nails. Juan’s family has been displaced 2 years ago and has been living in a basic hut in Medellin ever since. He now tries to build a larger house using anything he can find including used wood and nails. Suffering from hard economical status due to their displacement, people are forced to build their homes based on available materials.

Suninda Parilla Chavera (32) hanging laundry in her home in Quibdo. Suninda currently lives with two of her sons and supporting the other 4 which have to live with relatives in Venezuela after her husband was murdered by the guerilla four years ago forcing them to leave their village.

Lady Milena Londonio (12) and friends in her home in Barrio Pacifico in Medellin. Maria's family was evacuated 11 years ago from Salgar Antioquia by the FARC, being given 24 hours to pack they belongings and leave. They have lived in extreme poverty yet managed to survive in a small hut in the neighborhood.

Wilfrem Fernando Rojas (23,L) and his 6 months pregnant wife Ana Deisi Loais (19) in the hut they share with Wilfrem brother's family in ‘Comuna 18’ neighborhood in Medellin. Wilfrem and his family had to flee from Canas Gordos in October 2007 after being threatened by the guerrilla since Wilfrem joined the Colombian army. The families share a hut and run an illegal bakery in order to survive.

Pictures on a wall in a displaced family’s house in ‘El Hueco’ (the pit) neighborhood in Rionegro. The main wall decorations are often religious artifacts or militant pictures and memorabilia.

Displaced women from the department of Choco in Nuevo Amanecer neighborhood in Medellin. The government offered alternative housing in this neighborhood for displaced families, yet people that chose to move in had to pay large sums for basic housing.

A displaced woman and her daughter looking out from the windows of the hut in which they found refuge in ‘La Platanera 3’ area in the city of Pereira. The displaced have no other alternative other than build simple huts from whatever materials they can find in areas of low economical importance, and rarely receive any services from the government.

Displaced children look at a view of residential areas from Moravia neighborhood in Medellin. Following a growing influx of displaced people fleeing to Medellin the dumpster area of Moravia was inhabited by many who could not afford any housing.

A dog in front of a wooden hut surrounded by bagged recyclable trash in Moravia neighborhood in Medellin. The area which was once a dumpster was inhabited by displaced families without any financial means who try to survive by sorting the trash around them for recycling.

Jesus Armondo Rojas (35, R) and his wife Analihiya Peris Garcia (35, L) prepare arepas (local bread) next to their children in the illegal bakery they run in the lower part of their house in ‘Comuna 18’ neighborhood in Medellin. With no official recognition of their situation, many displaced people have to work illegally in order to survive.

Displaced girls in a house in 'Esfuerzos De Paz #1' neighborhood in Medellin. While many of the displaced hope to return to their homes in the future, they currently face a hard reality and are forced to try and build a new life elsewhere. Houses are decorated with pictures and religious artifacts trying to make them feel like a ‘home’.

A woman looks outs through the bars of the entrance to a shelter in Medellin. The WOW government organization operates 4 shelters in addition to 3 shelter operated by the UNHCR providing initial sociological-psychological aid for displaced families. Around 50 people live in this shelter. People are allowed to stay in the shelters for a period of a few weeks (a few months in the worst cases) after which they are expected to find a different housing solution using a humble departure grant.

Yurisai Palaso Palacios (9) playing with a doll as her mother Maria Parquala Palacios Chavera (33) works in the kitchen of their home in Quibdo. Yurisai's family was displaced from Bojaya after the massacre in the town's church in 2002 in which 119 people were killed and hundreds injured.

Maria Rubiela Cebelo Morales (52, L) with her daughters Linda Julien (13, R) and Tatiana Acebedos (4, C) in the basement of their house in Barrio Nuevo Caimalito near Pereira. Maria's oldest son joined a paramilitary group, yet after refusing to kill a friend to prove his loyalty, he was murdered together with his father. Maria fled with the rest of the children and tried to find a safe place next to Pereira. She lives with her three children and a new boyfriend.